Subcutaneous Biologically High Grade and Histologically Low Grade Fibrosarcoma Resection with Orbitectomy and Rotation Flap Reconstruction

Signalment: 7-year-old, MN bernadoodle

History:

This dog initially presented to me in late November 2023 with a rapidly growing subcutaneous mass, measuring 36.2 mm x 58.4 mm, on the dorsal to right dorsolateral aspect of the head. An incisional biopsy of the mass was read out as a fibroma. Wide resection of the mass was done a week later; histopathology of the mass was consistent with an incompletely excised (on the deep margin) biologically high grade and histologically low grade (so called hi-lo) fibrosarcoma.

The dog presented for a recheck exam in mid-January 2025 because of concern for a local recurrence. There was a palpable mass in the region of the surgical scar and a subsequent incisional biopsy confirmed a hi-lo fibrosarcoma. Three days prior to his planned surgery, a second mass appeared along the ventral aspect of the right lower eyelid. This was not physically connected to the recurrent mass. While a biopsy of this mass was discussed, his owner elected to proceed with surgery under the assumption that this was also a hi-lo fibrosarcoma.

Physical exam findings:

Recurrent firm mass dorsomedial to the right upper eyelid

Diagnostic and clinical staging tests:

CBC: no abnormalities

Serum biochemistry: mildly increased amylase and lipase

Punch biopsy: hi-lo fibrosarcoma

Three-view thoracic radiographs: possible but unlikely lung metastasis

CT scan: intrathoracic abnormality was an anomaly in the cranial vena cava, no evidence of lung metastasis; but evidence of bone invasion into the right frontal sinus

Notes:

A few things to consider with this case:

If the biologic behaviour of the mass (e.g., rapidly growing in this case) does not match the biopsy results (e.g., fibroma), then you should advise the owner that a more aggressive surgery may be required and a different postoperative biopsy result expected because the biologic behaviour and the biopsy results do not match.

Hi-lo fibrosarcomas are relatively common in the oral cavity, particularly in large breed dogs and especially in retriever breeds. This is my first case of a hi-lo fibrosarcoma in a location other than the oral cavity.

Treatment:

Wide surgical resection with 3 cm lateral margins and an orbitectomy-craniectomy for deep margins, including enucleation, and reconstruction with a rotation flap from the lateral face.

Outcome:

Hi-lo fibrosarcoma with complete excision (lateral margins varying from 2.5 mm to 2.0 cm and deep margins clean)

Distal flap necrosis

Video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4c6EIQnm73I&t=773s

Tags: #hiloFSA #FSA #orbitectomy #sinusectomy #reconstruction #rotationflap #distalflapnecrosis

Preoperative CT scan showing extension of the mass through the frontal bone into the frontal sinus (arrow). This surprised me to some degree. When discussing the possibility of local recurrence following incomplete histologic excision, I also consider what is deep to this margin and how likely are residual tumor cells, if actually present, to be able to propagate into a recurrent tumor. For this dog, I thought that this was unlikely considering the tissue deep to his original tumor was bone. But then this was a hi-lo fibrosarcoma and these are one of the most locally aggressive tumors in dogs.

Intraoperative image of the dog immediately prior to starting surgery. Note the subcutaneous masses along the medial aspect of the upper eyelid (recurrent mass) and lower eyelid. Lateral margins of 2 cm and 3 cm have been marked with a sterile marker pen.

An incision was done along the marked 3 cm lateral margins circumferentially around both the lower and upper eyelid masses.

This incision was then continued deeply to the level of the frontal sinus, zygomatic, and caudal maxillary bones.

A sagittal saw was used for the dorsal (frontal sinus) osteotomy.

The next step was an osteotomy along the zygomatic arch.

Once the zygomatic arch osteotomy was completed, the optic vessels and nerve were sealed and transected with a LigaSure.

Retraction of the caudal eye structures exposed the orbital bone to allow for an orbitectomy with a sagittal saw. This can also be done with a pneumatic burr or piezotome, but the sagittal saw is the most efficient of these power devices for performing these osteotomies.

The caudal aspect of the orbitectomy was completed with an osteotome and mallet.

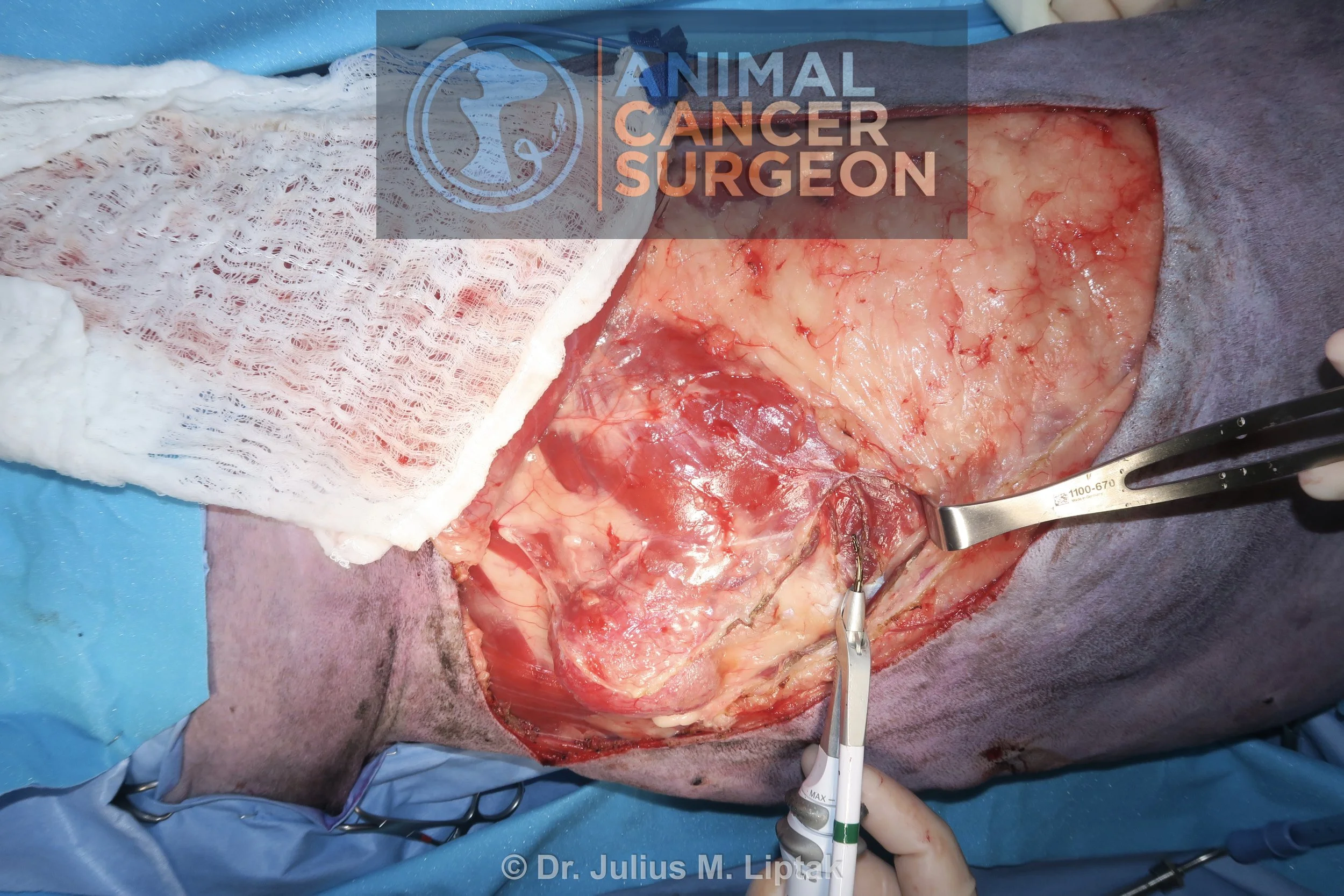

Appearance of the defect following completion of the wide tumor resection with en bloc orbitectomy-sinusectomy for deep margins.

A facial axial pattern flap was considered for closure of this defect; however, this flap was partially compromised because of the resection. As a result, a rotation flap from the lateral aspect of the face and neck was used for reconstruction. The borders of this flap were initially marked with a sterile marker pen (arrows).

An incision was then performed along the border of the rotation flap.

The rotation flap was then raised deep to the panniculus muscle to preserve the subdermal plexus. This is a random or subdermal plexus flap and so the blood supply is entirely dependent on preservation of the subnormal plexus blood supply rather than a named artery and vein like in axial pattern flaps.

The rotation flap was then rotated into the defect.

The position of the rotation flap was initially secured with tagging sutures.

The rotation flap was then sutured into place in two layers with a 2-0 Monocryl simple continuous suture pattern in the subcutaneous layer and staples for the skin layer.

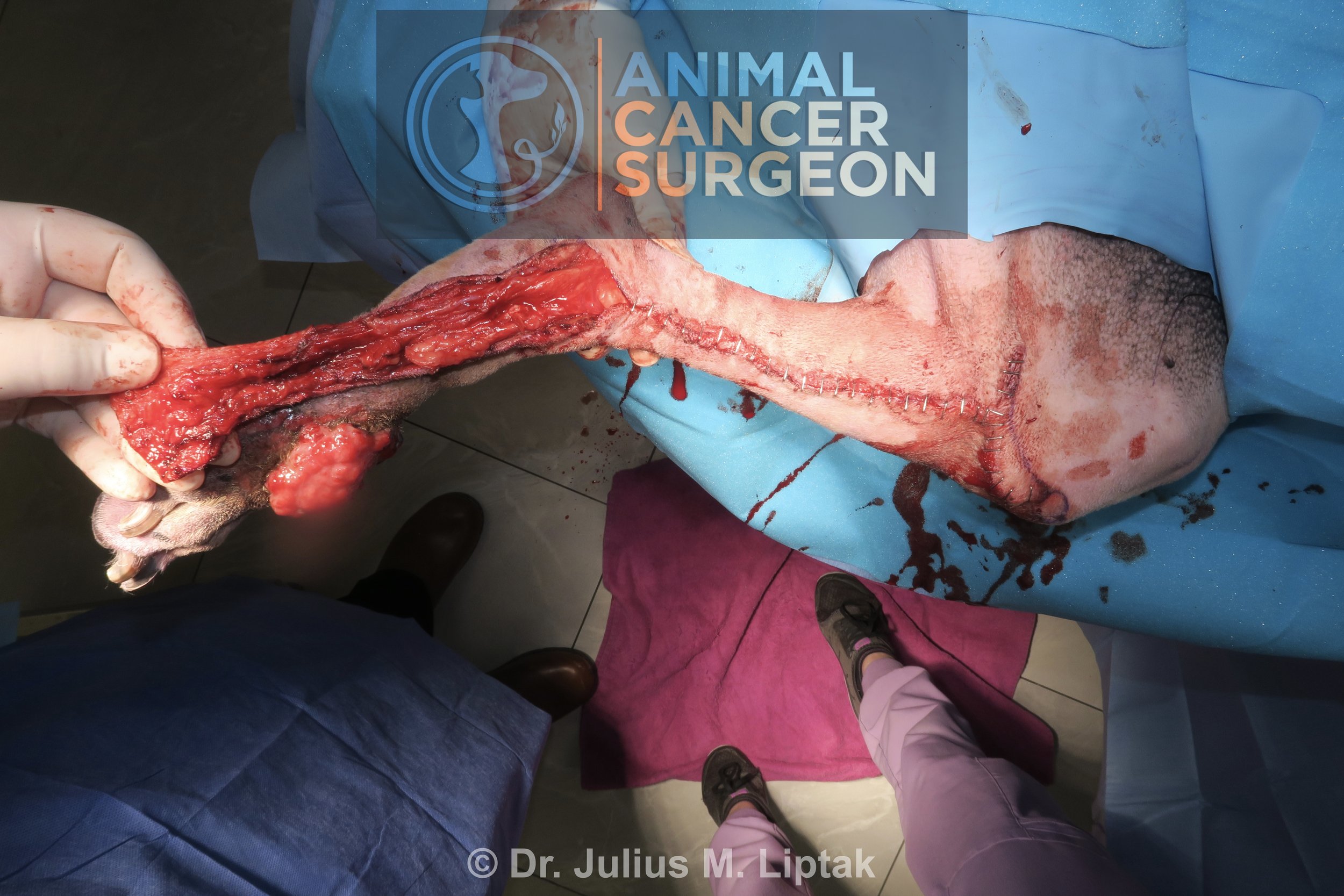

Postoperative specimen image with inked margins to help orientate the pathologist. Note the tumor extending through the frontal bone into the frontal sinus in the bottom left of the image.

Approximately 5 days after surgery, a well demarcated section of skin on the distal aspect of the flap was firm and leathery. This is classic for distal flap necrosis.

After anesthetizing the dog and clipping the area, there section of flap necrosis, again well demarcated, can be seen extending caudally along the flap border.

The necrotic areas of the flap were debrided and the flap resutured into position in two layers, 2-0 Monocryl simple continuous suture pattern in the subcutaneous layer and 2-0 Nylon in cruciate and continuous Ford interlocking patterns for the skin layer.