CLINICAL STAGING

Surgical oncology involves the surgical management of benign tumors and malignant cancers. The treatment of animals with cancer is well-established, and continues to be a growing field as improvements in preventive medicine and diets have resulted in our pets living longer and longer. Cancer is now the leading cause of death in older cats and dogs, and hence there is a need for everyone, from owners to family veterinarians to specialists, to be aware of the options available for the diagnosis and treatment of animals with benign tumors and malignant cancers. There are some important considerations when dealing with masses in animals, including preoperative biopsy, surgical margins, and histopathologic features of the tumor (such as tumor type, histologic grade, and histologic margins).

CLINICAL STAGING

Clinical staging involves additional diagnostic tests to evaluate whether a malignant cancer has metastasized. Clinical staging is not required for benign tumors. These additional tests are tumor-specific as different cancers will metastasize in different ways. For instance, malignant bone tumors will metastasize most commonly to the lungs and other bone; cutaneous mast cell tumors will metastasize to lymph nodes, spleen and liver; and apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinomas will metastasize to lymph nodes and lungs. Curative-intent treatment options are rarely indicated for animals with evidence of metastatic disease, and palliative treatment options are recommended in these cases. The World Health Organization classifies the clinical stage of malignant tumors based on the T-N-M classification scheme where T refers to the local tumor, N for regional lymph nodes, and M for distant metastasis.

The most important aspect of clinical staging for the local tumor is the maximal diameter of the tumor. Tumor size has prognostic significance for many tumors including oral malignant melanomas, mammary carcinomas, and apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinomas. There are other tumor characteristics which may have prognostic significance, such as ulceration of mammary carcinomas in dogs.

The regional lymph nodes are a common site for metastasis for many different types of tumors, including oral malignant melanomas in dogs, cutaneous mast cell tumors in dogs, histiocytic sarcomas in dogs, lung carcinomas in cats and dogs, mammary carcinomas in cats and dogs, and apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinomas in dogs. Traditionally, veterinary surgical oncologists have assessed the regional anatomical lymph node for evidence of metastasis. However, there are potential problems with this approach.

Firstly, palpation of the lymph node is a poor predictor of lymph node metastasis. In one study of 100 dogs with oral malignant melanoma, palpation of the regional mandibular lymph node had a low sensitivity (70%) and specificity (51%) for the prediction of lymph node metastasis. Of the dogs with evidence of metastasis to the lymph nodes, 70% had enlarged lymph nodes and 30% had normal sized lymph nodes. Of the dogs with normal sized lymph nodes, 40% had lymph node metastasis.

Secondly, the regional anatomical lymph node may not be the first draining (sentinel) lymph node and hence aspiration or excision of this lymph node may not be representative of the metastatic status of the lymph nodes. In one study of dogs with cutaneous MCTs, the sentinel lymph node was different to the regional anatomical lymph node in 40% of dogs. Furthermore, for cats and dogs with oral tumors, the only palpable lymph node is the mandibular lymph node, but metastasis to the non-palpable medial retropharyngeal and parotid lymph nodes has been documented in 45% of cats and dogs with metastatic oral tumors. Moreover, oral tumors can metastasize to the ipsilateral and contralateral lymph nodes. Surgical techniques have been described to excise the ipsilateral mandibular, medial retropharyngeal, and parotid lymph nodes, and both left and right mandibular and medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes through a single incision; however, this results in more extensive surgery with a greater potential for postoperative morbidity. Sentinel lymph node mapping was introduced in human surgical oncology to accurately identify the draining (sentinel) lymph node and minimize surgical morbidity associated with lymph node excisions. In a review paper entitled "Dramatic Innovations in Modern Surgical Subspecialties" in the Canadian Journal of Surgery (2010), sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy was described as the "most prevasive innovation in surgical oncology."

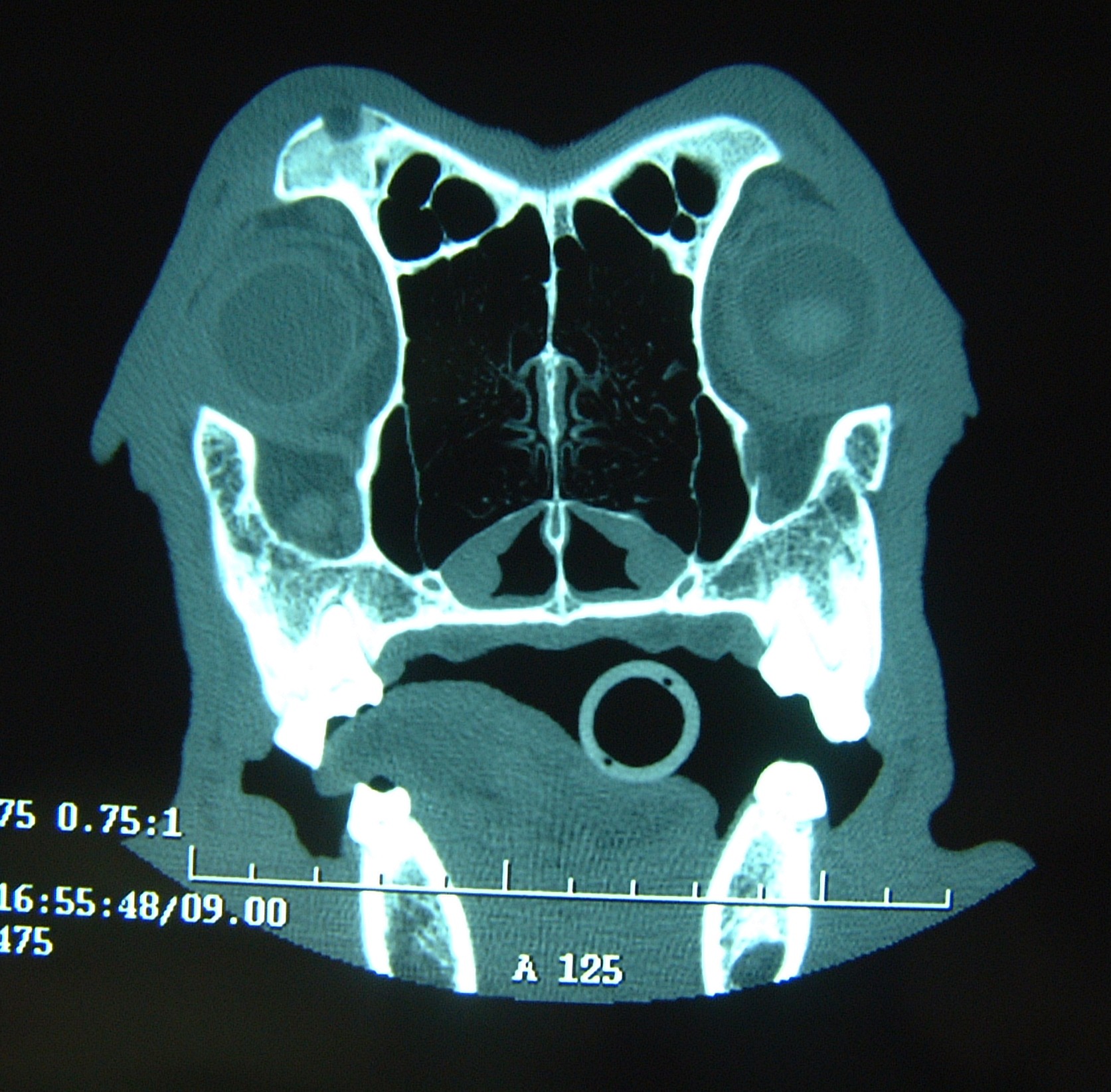

In people, sentinel lymph node mapping techniques frequently involve the use of radioactive material, such as preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and intraoperative radioisotope administration and detection with a gamma camera. These are not widely available in veterinary oncology, particularly outside academic hospitals. Dr. Herve Brissot has described a practical and accessible sentinel lymph node mapping technique for use in most veterinary referral hospitals. This involves peritumoral injection of a lipid-soluble contrast agent (Lipidiol) 24 hours prior to surgery (usually under sedation), regional radiographs or CT scan immediately prior to surgery to identify the sentinel lymph node, and then peritumoral blue dye injection during surgery to aide in intraoperative identification and excision of the sentinel lymph node. The sentinel lymph node is submitted for histopathology to determine if there is evidence of metastasis.

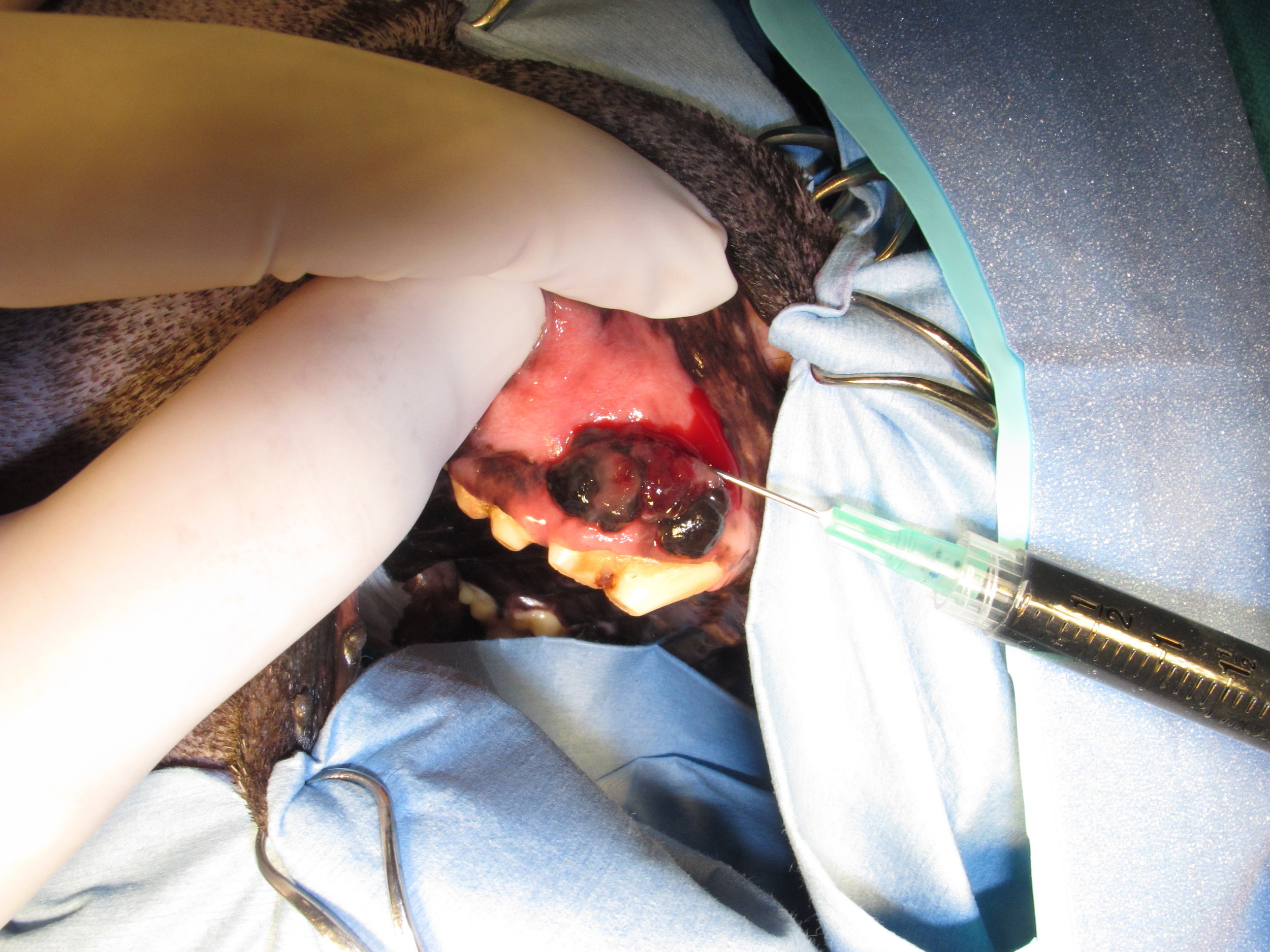

Four-quadrant peritumoral injection of Lipidiol, a lipid-soluble contrast agent, around a mast cell tumor on the pinna of a dog. This injection is performed 24 hours prior to surgery and usually under sedation.

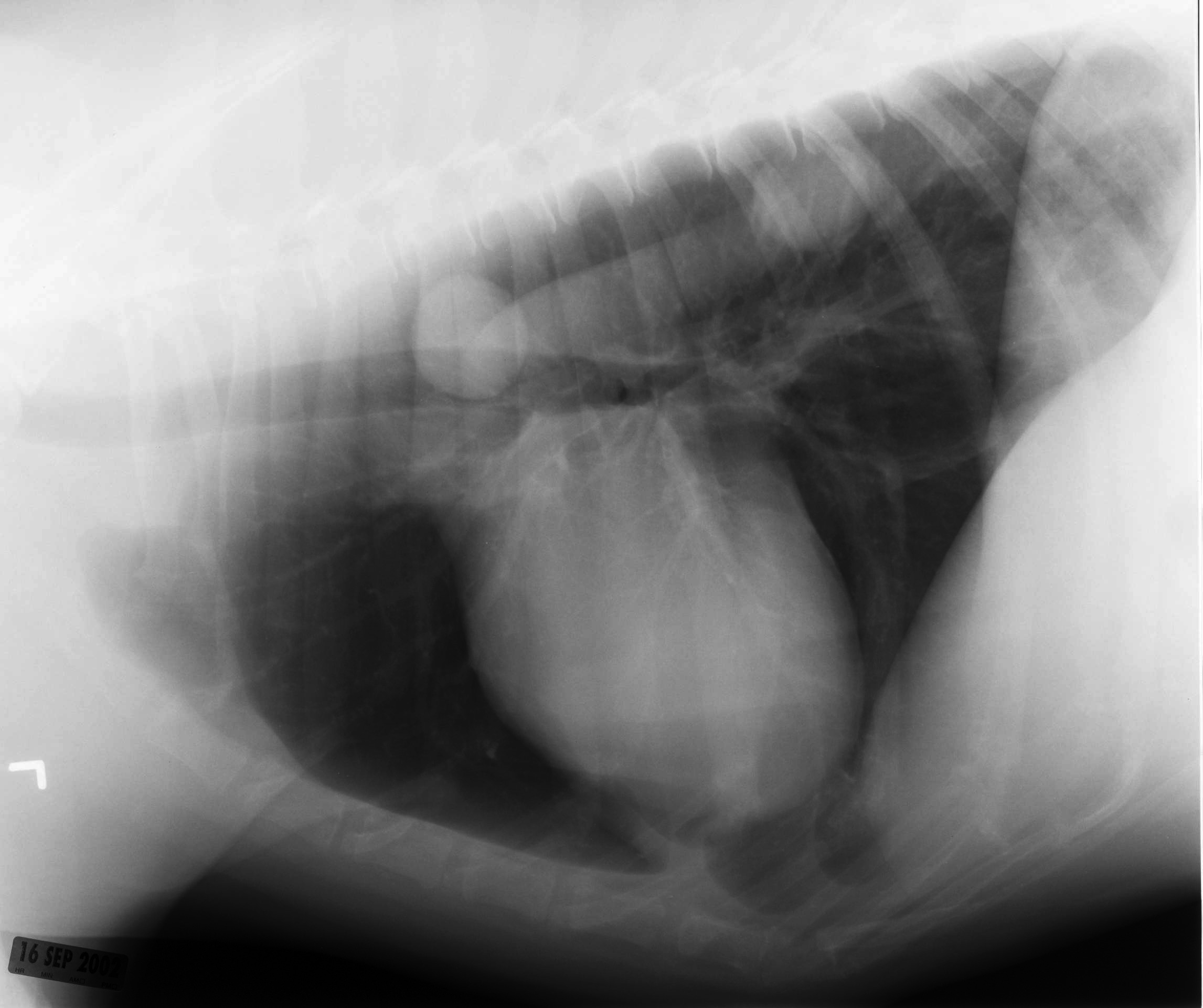

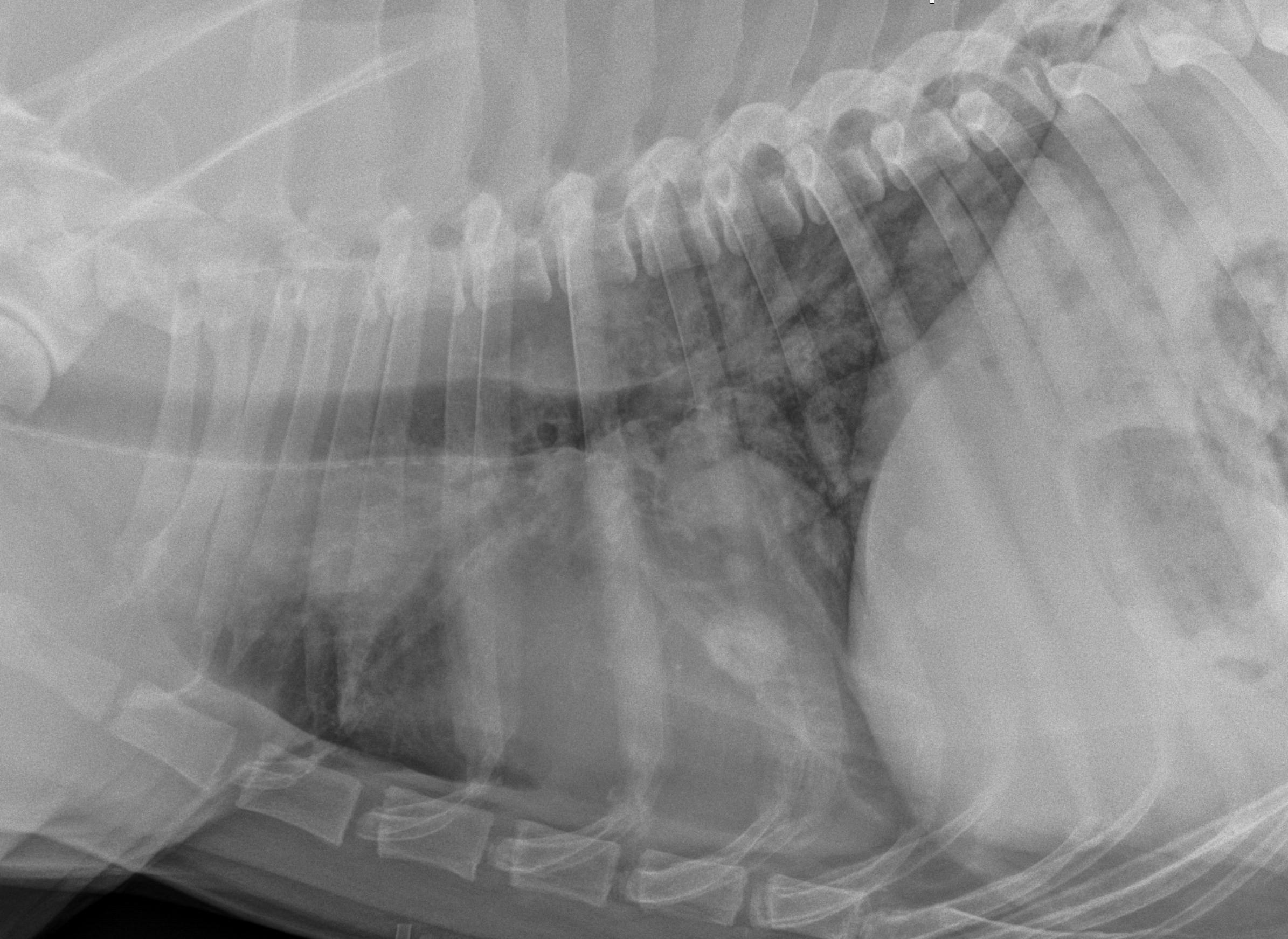

A lateral regional radiograph (prior to surgery and 24 hours after Lipidiol injection) in a dog with a digit squamous cell carcinoma showing the sentinel lymph node is the prescapular lymph node.

Intraoperative four-quadrant peritumoral injection of methylene blue to aide in identification of the sentinel lymph node during surgery.

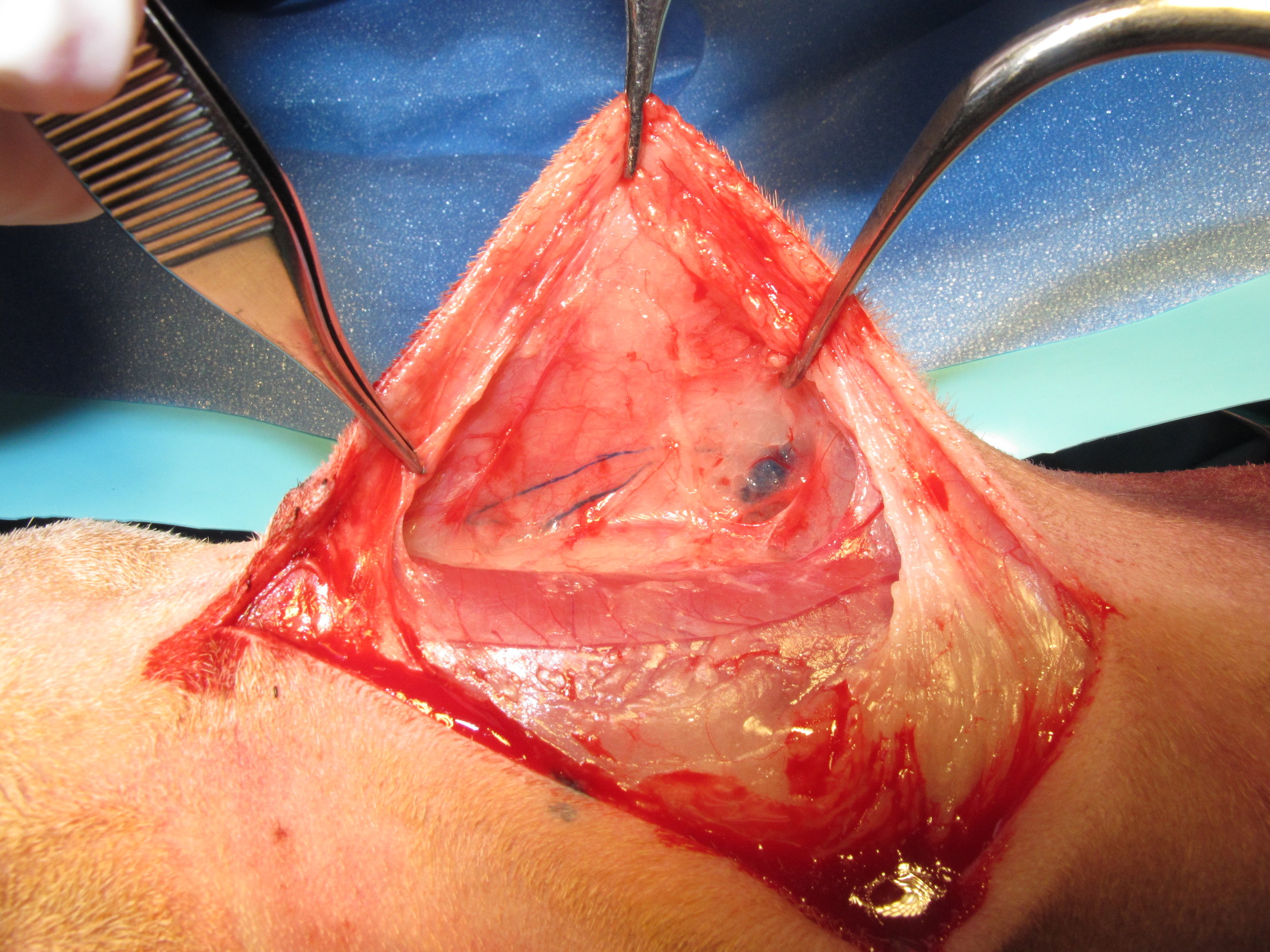

The methylene blue courses through the lymphatics to the sentinel lymph node and both are easily visible intraoperatively because of their blue discolouration.

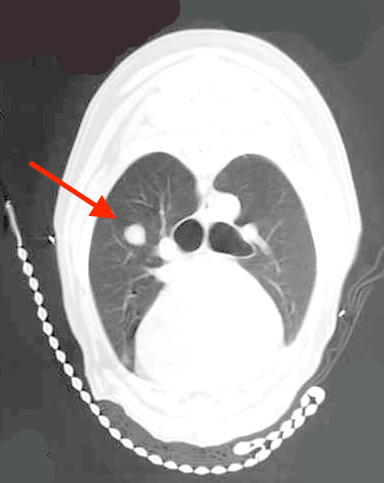

Distant metastasis is the last of the three components of the World Health Organization's T-N-M classification scheme. The most common site for distant metastasis is the lungs for most malignant tumors (except cutaneous mast cell tumors). Thoracic CT scans are preferred to three-view thoracic radiographs because pulmonary lesions as small as 1-2mm can be visualized on CT scans compared to 7-9mm on high-detail thoracic radiographs. However, thoracic CT scans are more expensive than three-view thoracic radiographs and thoracic CT scans are usually only performed in animals with tumors with a higher risk of pulmonary metastasis or when thoracic CT scans are combined with CT of another region, such as the head and neck for oral tumors or the abdomen for abdominal tumors.

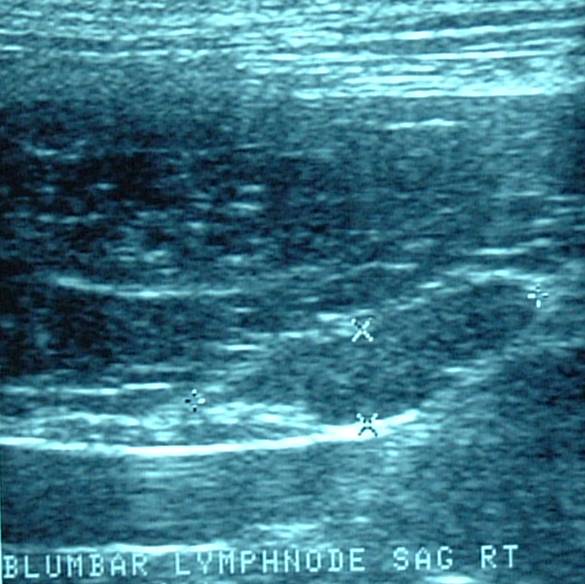

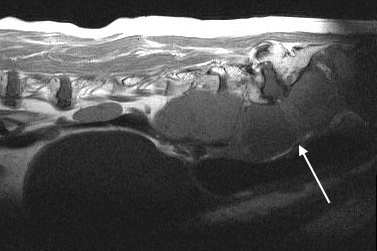

Abdominal CT or MRI scans are preferred to abdominal ultrasonography for evaluation of sublumbar lymph node metastases because of the difficulty in imaging the pelvic canal contents ultrasonographically.

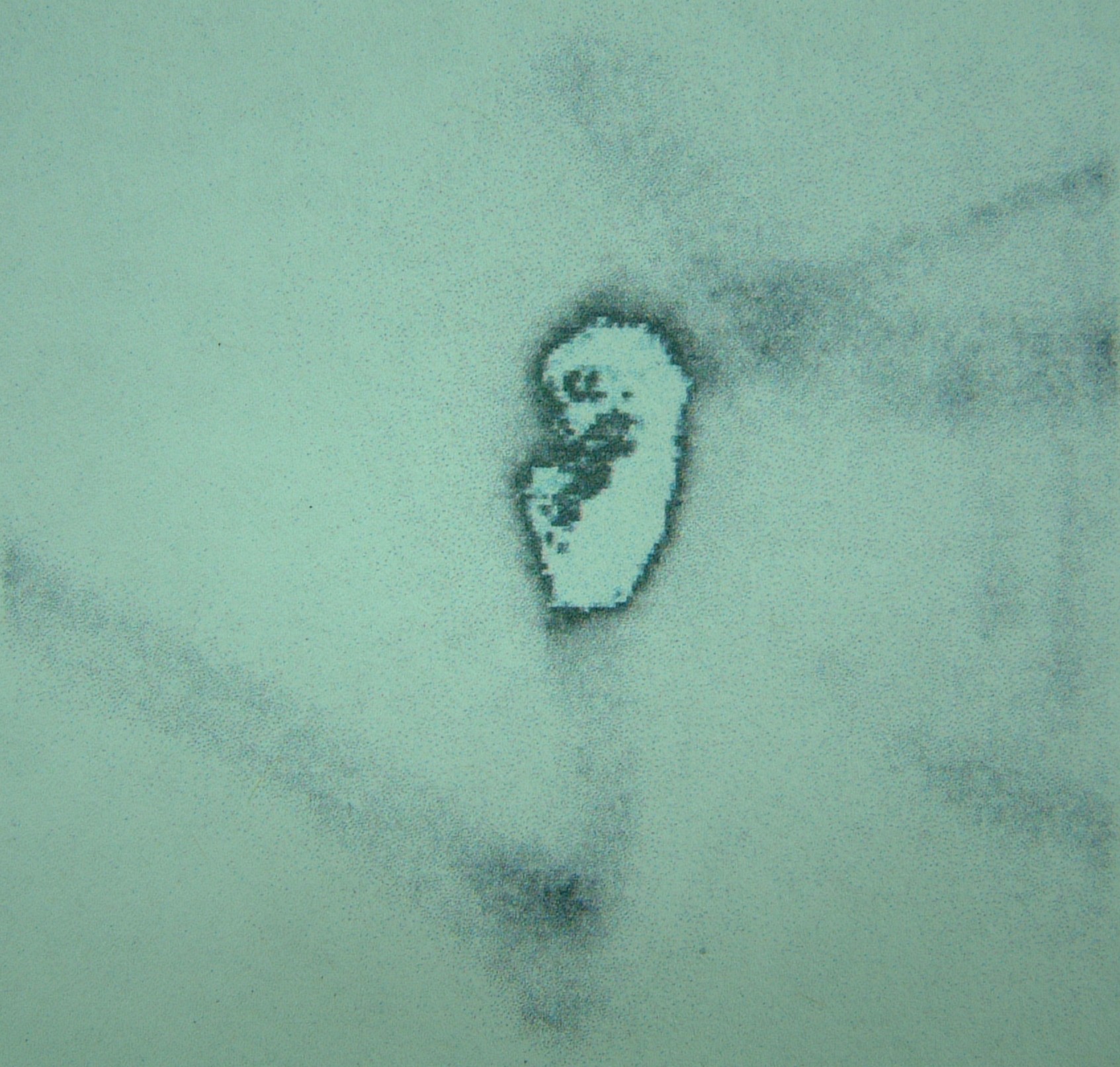

For animals with tumors with a higher risk of bone metastases, such as appendicular osteosarcoma and urogenital carcinomas in dogs, bone scintigraphy is preferred because of greater sensitivity for the detection of bone lesions than either whole-body radiographs or whole-body CT scans.

Last updated on 6th March 2017